tkatc

Well Known Member

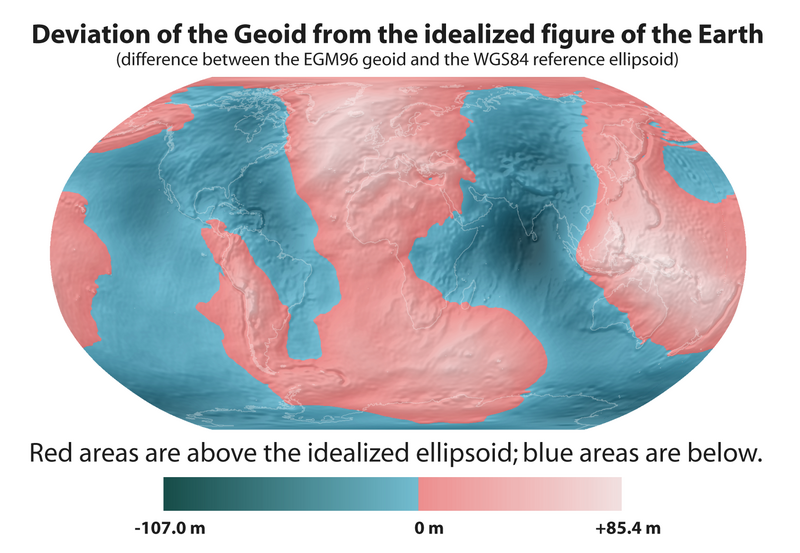

I've noticed a difference between my altimeter and my GPS altitude. I use a portable Garmin Aera 560 that is not wired to my encoder or anything like that. I never really give it much thought because I only fly VFR. I've been thinking perhaps I should clarify that difference.

I would like to discuss the following scenario in an effort to fully understand what my little box can and can't do.

You are flying VFR over the top. Beautiful up there and only another 40 miles til clear skies. Your trusty engine stops... You troubleshoot as much as you can but you cannot restart. You are sinking into the clouds below. Reported ceilings are less than 500'. You know you will be making an off field landing. You are confident you can hold the aircraft straight and level as you are descending at best glide through the clouds. As if you aren't rattled enough, the GPS starts screaming "OBSTACLE" or "TERRAIN". You were savvy enough to switch to the "Profile" view of your GPS but since the GPS altitude is different than your actual altitude, you're not sure what to trust. How do you decide which way to make corrections to give you the best odds of survival?

(This same discussion could be used if you got caught scud running, I don't want to discuss the decision to go VFR on top or VFR in low weather conditions. I want to discuss options and ways to use the equipment/information that is available should we ever find ourselves in such a dangerous situation)

I know these situations should be avoided at all costs but obviously they DO HAPPEN. I think it's better discussed now than to try and figure it out under duress.

I would like to discuss the following scenario in an effort to fully understand what my little box can and can't do.

You are flying VFR over the top. Beautiful up there and only another 40 miles til clear skies. Your trusty engine stops... You troubleshoot as much as you can but you cannot restart. You are sinking into the clouds below. Reported ceilings are less than 500'. You know you will be making an off field landing. You are confident you can hold the aircraft straight and level as you are descending at best glide through the clouds. As if you aren't rattled enough, the GPS starts screaming "OBSTACLE" or "TERRAIN". You were savvy enough to switch to the "Profile" view of your GPS but since the GPS altitude is different than your actual altitude, you're not sure what to trust. How do you decide which way to make corrections to give you the best odds of survival?

(This same discussion could be used if you got caught scud running, I don't want to discuss the decision to go VFR on top or VFR in low weather conditions. I want to discuss options and ways to use the equipment/information that is available should we ever find ourselves in such a dangerous situation)

I know these situations should be avoided at all costs but obviously they DO HAPPEN. I think it's better discussed now than to try and figure it out under duress.