A couple of years ago, I was removing an old fiberglass shower enclosure using an angle grinder. The thing slipped out of my hands due to the torque, and rattled its way to the floor ? but not before visiting my knee on the way down. Five stitches later, Louise convinced me that I needed to use my tools more wisely?it wasn?t the grinder?s fault, it was the user!

Well, the same thing is true with our well-equipped modern homebuilts chock-full of advanced avionics. Many of us can tell stories of under-experienced pilots getting themselves into nasty spots due to expensive equipment that they could afford ? but that they had not yet acquired the wisdom to use (note that airframe names and pilot occupations were left out on purpose to avoid going down an ugly road?).

A good example of the care to which these tools must be put is a recent trip we took from our home near Houston to the mountains of California ? Big Bear Lake, to be exact. Texas is suffering the worst drought in recorded history, so naturally, the one day that we had set aside for this trip saw a prediction for thunderstorms in West Texas and low clouds until late morning/early afternoon for the central and western parts of the state. We usually have enough fuel to make El Paso without trouble, but my number one rule when dealing with weather is that you can never have too much fuel (the better to run away with). Rule number two is that I rarely file IFR around thunderstorms, because I?d rather be out of the clouds where I can keep an eye on things (even though I am watching XM weather). But in this case, the low ceilings forecast made that a bit problematic ? MVFR on both sides of the Texas hill Country means IFR in the hills themselves (in general). Not a place to scud run. Of course, we wanted to leave early because we wanted to get across the convection area before anything major cooked up ? but earlier meant lower ceilings along the way.

The plan I settled on was to file IFR for the extreme west side of the Hill Country ? right up to about fifty miles short of the convection. I could retreat all the way home and have an hour?s reserve if I had to. We?d fuel up there, re-evaluate, and do the most sensible thing ? go on, go back, or sit and wait it out as seemed prudent. The first leg was simple ? good weather, clear until Austin, with a ?cleared direct Sonora? as requested after clearing Houston Approach?s airspace. After saying goodbye to Austin Approach and hello to Houston Center, we were cleared to descend at PD for Sonora, and broke out about 2,000 AGL so a procedure wasn?t necessary. It was good that this was a simple leg, because after checking to make sure that Sonora was a no-brainer on the weather, my attention was mostly diverted to the weather beyond ? what we?d be dealing with on the next leg.

We all know that NEXRAD radar in the cockpit is a god-send (at least those of us who have used it know that). We also know that it has limitations. Those limitations include latency (it can get old), and coverage holes ? there are still places with no useful radar coverage (mostly out west). Storms can hide in those holes, and that can be bad. The answer to both of these limitations is, of course, to spend some time watching in advance of arrival ? to look at the coverage and see how things develop. The time to deal with weather is not when you penetrate the first bad stuff ? it is way out in advance, when you have a time to study and develop a safe route through or around.

In this case, there was mostly one developing area of weather right around and west of Fort Stockton. It showed lots of green precip, some yellow, and was beginning to show the orange and read pixels that told me it was growing. There was additional green up towards Midland. Down south of Fort Stockton?well, that you have to take with a grain of salt ? the old ?radar coverage? thing. I have often been able to end-run these storms by going down around Marfa, but have also seen storms there where none were showing on the NEXRAD. The valuable thing about watching the NEXRAD pictures as we flew from Houston to Sonora was developing a feel for how fast things were building (or not) and how good the coverage was out west ? you can do this by looking to see if big, developed things magically appear at the edge of what you see, or if the development looks complete. I would never want to take on a line of weather that I was just shown, fully developed ? I want to know its history!

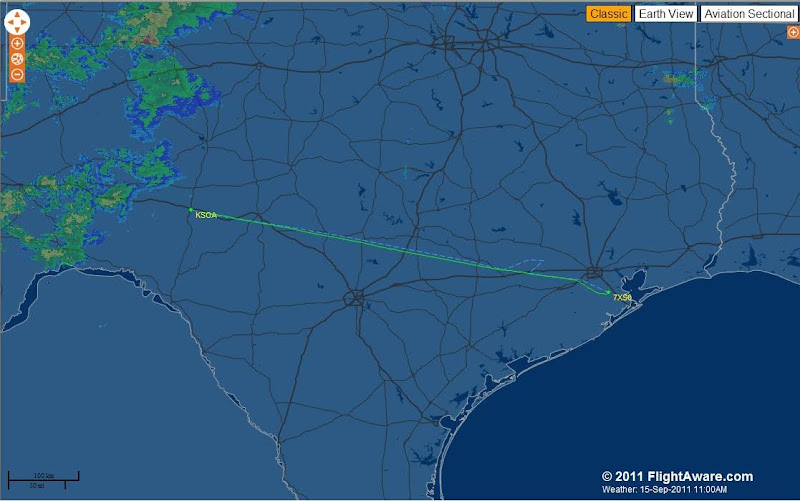

This shows the early part of the trip ? and what we were looking at ahead!

The next thing about being wise with tools is ?expecting to lose them?. Especially with single-string tools, like NEXRAD (yes, you might have two weather receivers ? as we did this trip ? but it?s still coming from a single source?) you need to know what you are going to do without them. This is why I rarely file IFR into an area of convection, because things can blow up behind you and cut off a planned escape route. And it is another reason to take a good look at the way the weather is developing In this case, I ?got the rhythm? of the weather and realized that we?d always have a good escape to the northeast, because there was a frontal boundary that was separating the good from the bad. So long as the area didn?t form a strong, thick line before we got there, we?d punch through the rain quickly and be through to the other side and freedom in no time.

Stay Tuned for Part Two.....

Paul

Well, the same thing is true with our well-equipped modern homebuilts chock-full of advanced avionics. Many of us can tell stories of under-experienced pilots getting themselves into nasty spots due to expensive equipment that they could afford ? but that they had not yet acquired the wisdom to use (note that airframe names and pilot occupations were left out on purpose to avoid going down an ugly road?).

A good example of the care to which these tools must be put is a recent trip we took from our home near Houston to the mountains of California ? Big Bear Lake, to be exact. Texas is suffering the worst drought in recorded history, so naturally, the one day that we had set aside for this trip saw a prediction for thunderstorms in West Texas and low clouds until late morning/early afternoon for the central and western parts of the state. We usually have enough fuel to make El Paso without trouble, but my number one rule when dealing with weather is that you can never have too much fuel (the better to run away with). Rule number two is that I rarely file IFR around thunderstorms, because I?d rather be out of the clouds where I can keep an eye on things (even though I am watching XM weather). But in this case, the low ceilings forecast made that a bit problematic ? MVFR on both sides of the Texas hill Country means IFR in the hills themselves (in general). Not a place to scud run. Of course, we wanted to leave early because we wanted to get across the convection area before anything major cooked up ? but earlier meant lower ceilings along the way.

The plan I settled on was to file IFR for the extreme west side of the Hill Country ? right up to about fifty miles short of the convection. I could retreat all the way home and have an hour?s reserve if I had to. We?d fuel up there, re-evaluate, and do the most sensible thing ? go on, go back, or sit and wait it out as seemed prudent. The first leg was simple ? good weather, clear until Austin, with a ?cleared direct Sonora? as requested after clearing Houston Approach?s airspace. After saying goodbye to Austin Approach and hello to Houston Center, we were cleared to descend at PD for Sonora, and broke out about 2,000 AGL so a procedure wasn?t necessary. It was good that this was a simple leg, because after checking to make sure that Sonora was a no-brainer on the weather, my attention was mostly diverted to the weather beyond ? what we?d be dealing with on the next leg.

We all know that NEXRAD radar in the cockpit is a god-send (at least those of us who have used it know that). We also know that it has limitations. Those limitations include latency (it can get old), and coverage holes ? there are still places with no useful radar coverage (mostly out west). Storms can hide in those holes, and that can be bad. The answer to both of these limitations is, of course, to spend some time watching in advance of arrival ? to look at the coverage and see how things develop. The time to deal with weather is not when you penetrate the first bad stuff ? it is way out in advance, when you have a time to study and develop a safe route through or around.

In this case, there was mostly one developing area of weather right around and west of Fort Stockton. It showed lots of green precip, some yellow, and was beginning to show the orange and read pixels that told me it was growing. There was additional green up towards Midland. Down south of Fort Stockton?well, that you have to take with a grain of salt ? the old ?radar coverage? thing. I have often been able to end-run these storms by going down around Marfa, but have also seen storms there where none were showing on the NEXRAD. The valuable thing about watching the NEXRAD pictures as we flew from Houston to Sonora was developing a feel for how fast things were building (or not) and how good the coverage was out west ? you can do this by looking to see if big, developed things magically appear at the edge of what you see, or if the development looks complete. I would never want to take on a line of weather that I was just shown, fully developed ? I want to know its history!

This shows the early part of the trip ? and what we were looking at ahead!

The next thing about being wise with tools is ?expecting to lose them?. Especially with single-string tools, like NEXRAD (yes, you might have two weather receivers ? as we did this trip ? but it?s still coming from a single source?) you need to know what you are going to do without them. This is why I rarely file IFR into an area of convection, because things can blow up behind you and cut off a planned escape route. And it is another reason to take a good look at the way the weather is developing In this case, I ?got the rhythm? of the weather and realized that we?d always have a good escape to the northeast, because there was a frontal boundary that was separating the good from the bad. So long as the area didn?t form a strong, thick line before we got there, we?d punch through the rain quickly and be through to the other side and freedom in no time.

Stay Tuned for Part Two.....

Paul